dedicated to fine Japanese sword fittings

The Ichinomiya Nagatsune Secret Marks; A journey of discovery by Chuck Granick

Before proceeding, I wish to make it very clear that the intention of this paper is not to be an in-depth and definitive analysis of either my hypothesis, or about Ichinoimya Nagatsune’s work. It is merely to present the known facts pertaining to my recent discovery in the hope that as a result, additional information will come forth from the collecting community. Should this occur, a forthcoming supplemental paper would then be prepared.

Through a most serendipitous series of recent events, a heretofore unknown secret about the Ichinomiya school of tosogu carvers may have come to light after 200 years. The story begins shortly after my acquisition of a wonderful pair of tai (sea bream) and hamaguri (clam) menuki carved by Ichinomiya Nagatsune ( figures 1 & 2 ).

The tai menuki is wonderfully executed in copper, with perfect scales and a delightful (and perfect) shakudo eye. While it is the tai menuki that is the first thing that is drawn to one’s attention, it is the other menuki that is, in my opinion, the true masterpiece. The large silver clam is wonderfully inlayed in shakudo in a hira-zogan style to create the illusion of shadow and patina. Further observation of the large silver clam reveals a perfectly executed and anatomically correct hinge. Further observation reveals the identical details on the silver and gold hamaguri as well. Both menuki have a wonderful original overall patina which surely was in place from the day that they first left Nagatsune’s studio over 200 years ago.

The set of menuki was forwarded to Richard George, a dear friend, professional photographer and fellow fittings collector. Richard’s task was to photograph the menuki for inclusion in an annual journal of tosogu. During this process, Richard noticed distinct marks on the back posts of the menuki ( figures 3, 4 & 5 ).

The posts or “kon” are typical of those found on most menuki, and are less than

2.3 mm ( 3/32” ) in diameter. They are also full length. Never having noticed the marks myself, I asked if he could email me an enlargement. Moments after sending me the photos, Richard noticed two additional and identical marks adjacent to both of Nagatsune’s mei, which were engraved on the visible side of the menuki in a style called kibata-mei ( figures 6,7 & 8 ).

The stamps are less than .75 mm ( 1/32” ), which is equivalent to that of a thick pencil point! They are recognizable to the human eye as nothing more than a surface ding or scratch. A 40 power loop however clearly reveals a distinct hand cut stamp which is intentionally and carefully struck at all 4 locations. Before revealing a hypothesis on the purpose of these marks, a brief history of Ichinomiya Nagatsune and his school is important to the understanding of same.

Ichinomiya Nagatsune was born in 1721 and died in 1786 at the age of 66. Along with Otsuki Mitsuoki and Tetsugendo Shoraku, he is considered to be one of the 3 greatest Machibori masters from Kyoto in the Edo period, and was famous and collected even during his lifetime. These 3 master carvers from Kyoto were for the most part working for a sophisticated clientele of nobility and wealthy industrialists. Wakayama Takeshi, one of Japan’s foremost tosogu scholars, personally considered Nagatsune to be one of the 4 or 5 greatest carvers in all of Japan. It has recently come to light that many of the master carvers of the machibori tradition were quite well educated. The relatively obscure subject matter frequently chosen by Nagatsune for his motifs would certainly indicate that he was quite well read. It is also known that Nagatsune studied drawing under the great master painter Maruyama Okyo, and those acquired skills are clearly evident in the wonderful sketchbooks that he produced, as well as throughout his entire body of work.

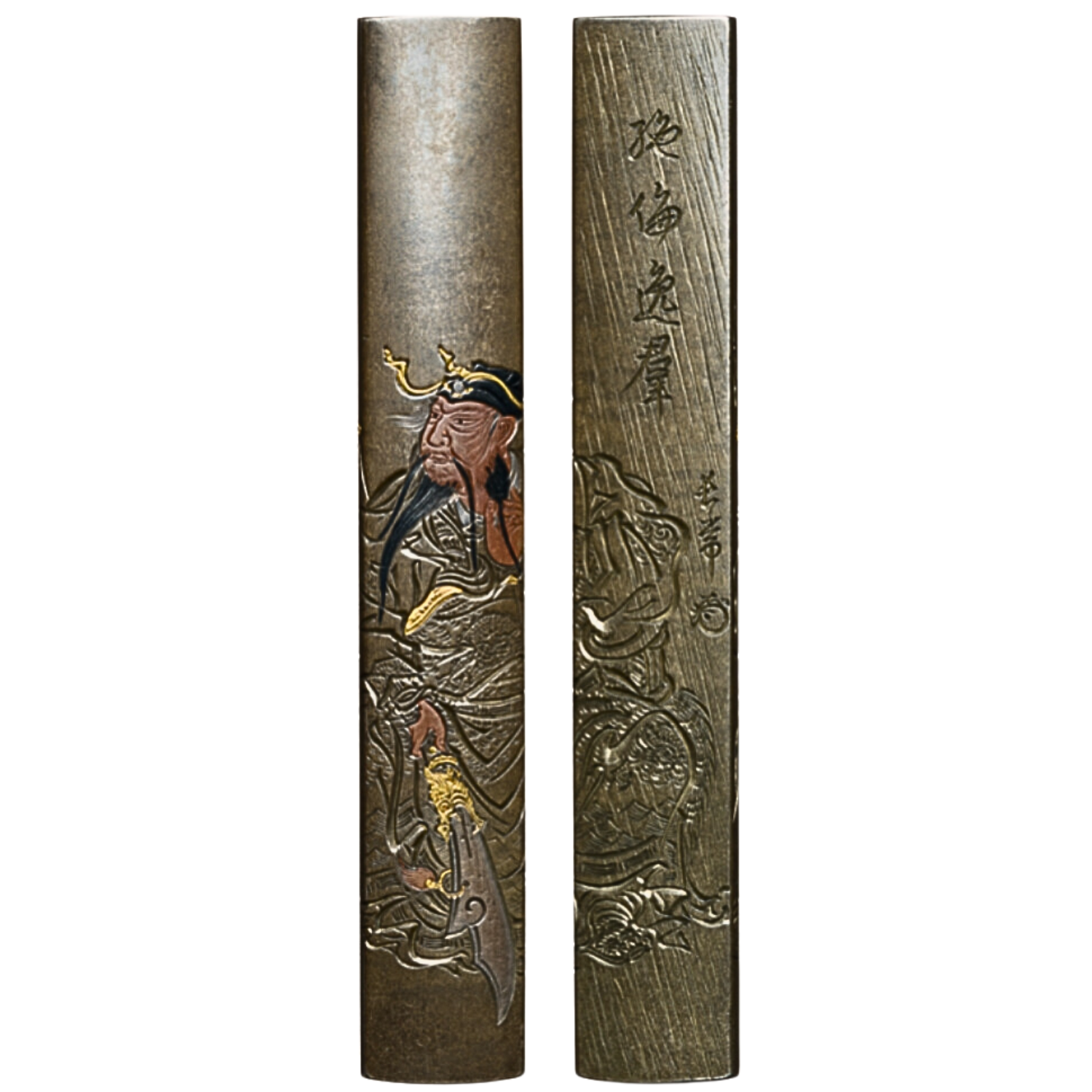

The style of work for which Nagatsune is most famous is called katakiri-bori. This style is basically the manipulation of various width 5agine chisels to make cuts at both free flowing angles and various depths to create a subtle and yet powerful result. Nagatsune was for all intents and purposes making the equivalent of brushstrokes with his chisels. Yokoya Somin, Nagatsune’s counterpart in Edo ( Tokyo ), was also utilizing the same katakiri-bori style of carving. Nagatsune however added mixed metal hira-zogan flush inlays to accent various details of his work, thus adding an additional level of interest ( figures 9 & 10 ).

Upon inspection of Nagatsune’s sword fittings executed in this manner, one’s first impression is that his work is somewhat naive and simple. Nothing could be farther from the truth, as he was truly a genius in creating emotion through the subtle manipulation of his chisel. Nagatsune had one chance, and one chance only to create the subtle facial details and emotions of the fascinating characters in his original motifs. The slightest error in the movement of his hand would destroy his efforts. He clearly was a master in both the design of his motifs, and in their execution. Nagatsune also produced a large volume of work in the many varied machibori styles of his contemporaries ( figures 11 -15 ).

While many of these are also true masterpieces, it is his work in the katakiri-bori style that one most readily associates with Nagatsune.

For the past 5 or 6 years, Ichinomiya Nagatsune has been a dominant focus of my collecting. As such, the newly discovered stamps on my tai and hamaguri menuki had most certainly piqued my interest. The study of Nagatsune and his school is a somewhat difficult and frustrating undertaking, as the available information on the subject is predominantly in the Japanese language. What limited information that is readily available in either the English or the Japanese tosogu textbooks is unfortunately exceedingly redundant from one source to another. Ichinomiya Nagatsune: Tsuruga Ga Hokoru Kin no Takumi is the only dedicated monograph available on Nagatsune. While a good basic sourcebook, it does not provide a depth of insight into the subject matter.

With that said, just prior to the discovery of the “mystery” stamps on my menuki, I was fortunate to have acquired an older tosogu book, Karei na Toso Kogei, from the library of my dear friend Kunio Izuka. Kunio, who tragically passed in 2020, was the Sensei of the New York Token Kai / Metropolitan NY Japanese Sword Club since its inception. This Japanese language book by Wakayama Takeshi amazingly contained a chapter of over 100 pages dedicated to Nagatsune and his students. From what I was able to discern, there appeared to be information on the school that had heretofore been unknown. I shared the chapter with Darcy Brockbank, and through his good graces, Markus Sesko was retained to translate the chapter into English for study purposes.

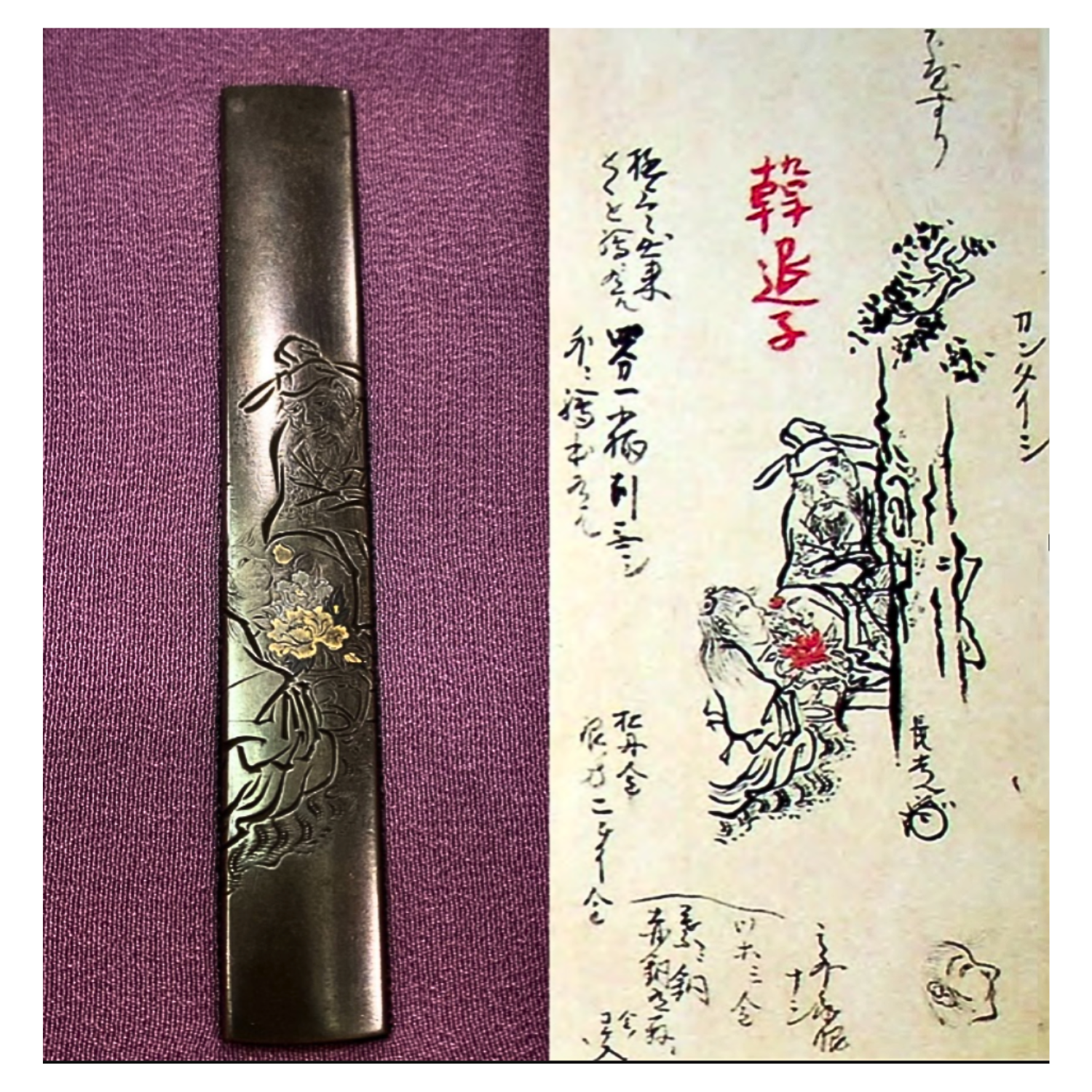

A first draft of the translation revealed many fresh documents and insights from Wakayama. As mentioned previously, Nagatsune’s left behind a wonderful series of detailed sketchbooks of his design motifs. ( As an aside, these sketchbooks were subsequently obtained by Kano Natsuo. While many collectors consider Natsuo to be the greatest carver in Japanese history, it was Nagatsune who Natsuo considered to be the best.) The sketchbooks were compiled in 1787 by Ichinomiya Nagayoshi, Nagatsune’s grandson and heir, under the title of Horimono Echo. In one particular passage of Wakayama’s chapter, he discussed Nagayoshi’s opening remarks to the sketchbooks wherein he (Nagayoshi) mentions that;

“… many forgeries of my grandfather’s work are circulating, and our family is thus often approached for authentication. Thus, my family is issuing appraisals and adds seals of authentication to boxes. However, often the items in these boxes are switched and therefore utmost caution should be used with such. In this sense, the sketchbooks should serve as an aid to identify the authentic first-class work of my grandfather”.

It is these statements by Nagayoshi that is key to my hypothesis about the curious stamps.

As I had mentioned earlier, one’s first impression of Nagatsune’s work is that it appears to an uneducated eye to be simple and naive. Until one studies numerous examples of his work in katakiri-bori, that technique appears to be quite easy to copy. From the numerous forgeries that were carved both during and after his life, it would appear that the carvers faking his work apparently thought so as well. While the most skilled forgers came exceedingly close to duplicating his work, the less skilled carvers failed miserably. Unfortunately, not every samurai or merchant looking to acquire Nagatsune’s work had a sophisticated eye, and consequently many, many forgeries came into the marketplace.

With so many gimei pieces being circulated in the marketplace, and with the authentication documents being swapped out to accompany the fakes, it is not unreasonable to assume that Nagayoshi would therefore go one step further and begin to secretly and permanently mark the shoshin ( genuine ) Nagatsune fittings that were coming in for authentication. This would allow the family and the subsequent Ichinomiya generations to tell which pieces had already been vetted by their family. The mainline Goto masters did the same thing when a later generation was retained to authenticate the work of an earlier generation. After doing so, they would issue a formal origami to the tosogu owner as proof of same, and make a duplicate origami for the Goto family records. At the same time, and unbeknownst to that owner, they would carve a secret mark at a prescribed location on the fitting known only to the Goto family. It has been assumed that these marks were kept a secret by the family so that if a subsequent Goto generation was asked to authenticate a sword fitting, he would instantly know that that fitting had already gone through their vetting process. He could then check the Goto family records, and duplicate the earlier results. He certainly would not have wanted to contradict the attribution of an earlier generation’s kantei. For over 400 years, the 17 generations of the mainline Shirobei Goto were know for their scrupulous and private record keeping. The knowledge of their secret marks was only revealed in the late 19th or early 20th century. These Goto secret marks were only tiny “v” chisel cuts applied in secret but prescribed locations. It is our suggestion that Nagayoshi went one step further than the Goto for the vetting of his grandfather’s work, and created a secret microscopic kakihan or chop stamp. This stamp left a mark that was even smaller than the Goto secret marks. Even if inadvertently discovered, Nagayoshi’s stamp would have been exceedingly difficult to recreate. Also as stated, the Nagayoshi stamp is invisible to the naked eye, so the chance of discovering it was exceedingly small.

To add credence to this theory, I solicited the assistance of two close friends who are also collectors of works by Nagatsune. My hope was that the stamps on my set of menuki were not unique. I sent magnified images of the chop to both, and asked if they would check the Nagatsune examples in their collections for the mark. Within short order, I received a call back with the good news that there were two (2) items in their collections that had the identical stamps to that on my tai and hamaguri set of menuki.

The first of these two was a fuchigashira that had the stamp on the fuchi just below Nagatsune’s kao ( figures 16 & 17 ).

For all intents and purposes, this was the identical location to the mark on my menuki. The fuchigashira is a lovely joint work or “gassaku” executed in the katakiri bori style, with the fuchi signed at the usual location on the “tenjogane” ( the flat interior surface ) by Nagatsune, and the kashira signed “kibata-me” ( the visible or exposed outside ) by Nagayoshi. Of the pair, only the Nagatsune fuchi had the secret stamp. No secret stamp was present adjacent to Nagayoshi’s mei. If my supposition is correct, Nagayoshi would not have stamped a kashira that he personally made, as it would have been presumptuous to authenticate anything but his master’s work.

The second of these two privately owned items containing the stamp was a shibuichi tsuba which, like the fuchikashira, was also carved in Nagatsune’s classic katakiri bori style ( figures 18 & 19 ). The secret stamp on this tsuba was once again struck just below Nagatsune’s kao. It is important to note that all three of these pieces exhibiting the secret stamp have been vetted and papered by the NBTHK, and examples of the all three motifs are contained in Nagatsune’s original sketchbooks. As such, they are all genuine Ichinomiya Nagatsune pieces.

As to my set of tai and hamaguri menuki, one might ask why Nagayoshi would have marked them in 4 locations. The stamps on the posts would not be visible if the set was mounted, while the stamps adjacent to the kibata-mei would be. As such, the menuki could be readily reevaluated by the Ichinomiya family regardless of whether they were mounted or unmounted.

One further point worth mentioning about the secret mark is the time frame in which the stamps were applied to the posts. Magnification of the ends of the full length posts clearly show the original file marks which were applied as part of Nagatsune’s finishing process. Images of the end post stamps were forwarded to another fittings collector who is also a professional jewelry maker for over 45 years. In his professional opinion, the stamps were definitely applied at a point subsequent to the original fabrication of the posts. He advised that when struck, the stamp would have compressed and obliterated the file marks on the bottom of the stamped impression, while those file marks remaining on the outer edges of the stamped area would have been “stretched”. The mark is clearly as described, thus evidencing that Nagatsune’s filing and finishing processes on the menuki posts had proceeded the application of the stamp.

This gives further credence to the stamps as having being applied at a later point in time by someone other than Nagatsune himself.

The 16 authentic ( NBTHK vetted ) Nagatsune pieces available for immediate inspection by myself and associates revealed only 3 containing “secret” stamps. This is not an unreasonably low number to formulate a hypothesis, for if my conjecture is correct, only those pieces that were brought in to the Ichinomiya family for later authentication would have received the secret stamp. It also is to be assumed that Nagayoshi would have only started to use the stamp after it was discovered that unscrupulous dealers were swapping out his family’s “special authentication boxes”. Searching for other examples of the secret marks in the numerous photos of Nagatsune fittings in tosogu books is unfortunately futile, as the stamp is too exceedingly small to be visible in anything but a greatly enlarged high resolution photo or with a 40 power loop.

This “secret mark” theory was presented to a small but well respected group of a dozen fittings collectors around the United States. The overall and mostly unanimous feeling was that the stamp was indeed used as part of the vetting process by Nagayoshi or another Ichinomiya master. One member of the group suggested that perhaps the mark was a collector’s stamp. It seems highly unlikely however that a collector with no carving skills would risk damaging a masterpiece with an improperly struck blow from his hammer.

It is the hope of this article that tosogu collectors around the USA and the world with authentic Nagatsune fittings in their collections will check their examples for the mark. It would also be exceedingly interesting and exciting to locate one of Nagayoshi’s original authentication boxes.

I wish to thank the following dear friends for assisting in the formulation of this hypothesis;

Richard George

Darcy Brockbank

Markus Sesko

James Lawson

Fred Geyer

I also would like to thank both Mike Yamasaki for starting me on this journey by selling me my first Nagasune fitting many years ago, and Peter Klein for convincing me to buy it!

Hi,

I recently bought a Fuchi signed Nagatsune. I am no expert on tosugu and I was wondering if you would like to offer an opinion on this piece?

Best wishes,

Edward Simpson

What an exciting find. The stamp itself looks to be the character 正, which itself means ‘correct’. This is also the first character for the term ‘shōshin’ (正真) which is used to designate an authentic signature. So I think the theory that these were applied as a means to validate the signature is the most plausible one.

Hi Dr. Shuttleworth,

First of all I must apologise for my late reply, I have no excuse other than poor time management on my part. I am delighted that you think my Fuchi is a genuine item, it is a work of great skill and it came off a sword I bought in auction. That sword was in a fairly sad state and has now been remounted. I am not really a fittings collector so I may move this Fuchi on soon to someone who will appreciate it.

My very best wishes and thank you for your time.